Very smart piece by Janani Balasubramanian in The New Inquiry 0n the move in the US by the Federal Drug Administration to reclassify human excrement as an ‘Investigational New Drug.’ I actually tweeted about a similar story on the BBC website last year, which outlined the growth in the use of fecal transfers to treat a wide variety of auto-immune conditions.

In short: what doctors are realising is that shit is very fertile. It contains vast numbers of bacteria that help with healthy gut function. What a fecal transfer does (usually via an enema) is reintroduce proper levels of these bacteria into the digestive tract.

Gross, huh? Well, this is one of the core issues: the need to get over the shame long-associated with everything surrounding defecation:

Collective shame around shit looms so large as to seem like an unchangeable fact, even as fecal transfers offer significant curative properties. How many of us shit as discreetly as possible to avoid being heard? How many avoid shitting in front of intimate partners?

And yet, in our flight from shit, we’ve created overly-pure spaces that have ended up as profoundly unhealthy. This is the key sociological parallel: what fundamentalist communities do is work to shit out all that they find impossible to digest, but the result of this is a weakened body that attacks itself:

Whether what’s pushed away is shit, people, or disturbing ideas, the agent of this rejection is always an asshole.

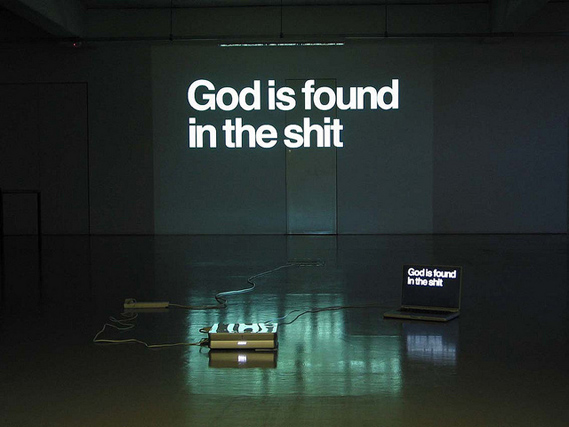

One of the more significant seams that Vaux explored back in the early 2000s was based on the idea that ‘God is found in the shit.’ It is our relationship to this alterity, our ability to reintroduce it into our bodies, that is key to an empathetic and healthy society.

Balasubramanian goes on to reference Mary Douglas’ Purity and Danger, which was a great inspiration for my first book The Complex Christ. Douglas writes:

Where there is dirt there is system… uncleanness or dirt is that which must not be included if a pattern is to be maintained.

What we classify as ‘dirt’ is important, as it highlights what our systems of purity are, what criteria we use to judge who’s in and who’s out. Yet these dirt boundaries are often complex and moveable. A can of coke dropped in a newly-ploughed field is litter, is ‘dirt.’ Yet put the same can in the fridge, and now it is the earth from the field that is dirt. It is ‘matter out of place.’

Thus this move to reclassify shit as fertile medicine requires us to think about the place of ourselves and others in the world. Which bodies do we consider out of place? Women bishops? People who are gay? Immigrants? The attempts to purify spaces by excluding these ‘dirty bodies’ has only resulted in dis-ease and decay.

Shit can be shared, and shit can heal, because it is the mark of our contiguity with our environments. No one lives autonomously, even within a single body.

What we must do is begin to understand it as a gift, as an integral part of our cycles of involvement with our ecosystems. One of the phrases I’ve been mulling recently is from Gary Snyder’s book The Practice of the Wild:

Each one of us at the table must recognise that one day we will become part of the meal.

The less bucolic configuration of the same idea of ourselves as parts of larger cycles of material is the more scatalogical one:

Each one of us in the bathroom must recognise that one day we will become part of the shit.

When our bodies decay they will become the ‘dirt.’ They will be disposed of in a manner that separates us from that which remains living. We will be excluded, expelled, discharged. Important then that we live in a manner that is reflective on our dirt boundaries, and considers carefully the ways that our attempts at purity exclude. Sterile surfaces are those upon which nothing can live. We should avoid this.

[Thanks Darryl Schaffer for putting me on to the article]